Behind the Headlines

“Three fast-food workers were found shot to death Wednesday . . .”

“An explosion caused by a leaking propane tank leveled a house, killing a woman . . .”

“A young actor was found dead in a hotel . . .”

“A former long-haul trucker was executed by injection Wednesday for raping and stabbing three women . . .”

“One body was discovered Wednesday in the wreckage of a pair of collapsed buildings . . .”

How many deaths was that—four, five, no seven? I scanned the news in the local paper as I sipped my hot coffee and nibbled the remaining crust of my whole grain toast. How could I just sit there eating—so uninvolved, so unaffected by the suffering of so many? Did the weight of all that pain only justify a few lines of ink and newsprint, read today, tossed tomorrow? I had become callused, hardened, I suppose, by the constant barrage of reported crime, death, accident, and war. I’d become somewhat immune to the suffering of sons and daughters, fathers and mothers. People just like me.

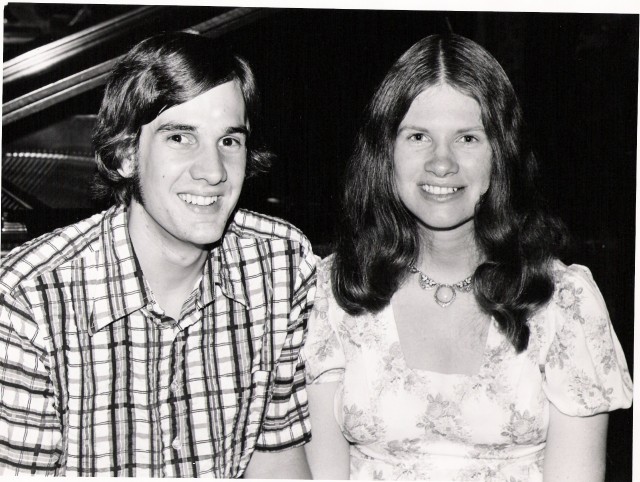

I wondered if someone had picked up the Atlanta paper in May of 1979, and over coffee, skimmed the tiny headline about a young man in a motorcycle accident who spilled half his bright red blood on Bankhead Highway.

My eighteen-month-old son was in his highchair, screaming and pasting spaghetti to his hair. The phone rang. A woman identified herself as a nurse from Cobb County General Hospital: “Your husband has been involved in a motorcycle accident. He may have a broken leg.” I proceeded to ask perfunctory questions, and she proceeded to give directions and very little specifics.

I knew in my heart it was bad. My mind flashed an image of Kelly flying through the air. My son still screamed. I felt numb. Immediately, I arranged for a baby sitter and a ride to the hospital. I didn’t dare drive. I moved in and out of a haze of tears and desperate “please Gods.”

Word spread, and friends gathered, keeping the long vigil with me on hard plastic waiting room chairs. Tears, phone calls, prayers, blurred conversations, heaviness on my chest. We waited and waited and waited.

I saw him for a brief moment as they wheeled him down the hall to recovery in ICU. He was barely lucid, sunken, gray, and vacant, but he was alive. And he still had his leg—what was left of it.

This was the beginning, the beginning of numerous reconstructive surgeries, infection, physical and spiritual pain, depression, physical and spiritual therapy. For others, the crisis was over. They moved on to the next headline. But for us, the crisis ebbed and flowed for months and years and still affects our lives today. The newspaper headline became an archive while the pain wore on.

Are we like the ancient Romans and their gladiators; do we get some kind of vicarious pleasure out of the suffering of others? Or is it just that we hold headlines at an emotional distance, cluck our tongues, and inwardly thank God that this tragedy didn’t touch our home?

“Five perish on deadly day in Valley.”

“Twelve special-needs adults suffered minor injuries when the bus they were riding in collided with a vehicle . . .”

“A man was killed Thursday morning when he allegedly ran a red light . . .”

I can’t help in every situation. I may not be in a position to touch directly the lives I read about, but I need to care. I need to deeply care that someone in my community this night comes home to an empty house—comes home to a future alone after great loss. Someone faces months of protracted pain and recovery and so many “whys.” There is someone weighted with guilt over choices made and consequences earned, someone who wishes they could relive the moments.

I need to care. I need to pray for the peace of God to intervene and invade these broken lives, these broken hearts. I can pray in a knowing way, as I remember what it feels like to live behind the headlines.

No comments:

Post a Comment